Writing Formatter Extensions for .NET Interactive

Published 2020-11-30

.NET Interactive is a pretty new and exiting way to do exploratory development with F#. One important thing about exploration is the visual inspection of your outputs. What fields are in those records? What's the content of this list? How would this data look in a bar chart or in a scatter plot? All questions we can answer by looking at formatted outputs. But how does .NET interactive know how to display these outputs for us in a form, that tells us what we need to know? In many cases (most cases even when you look at how big the .NET ecosystem is) it simply doesn't. But that's ok because we have the tools to write our own formatters and share them with the rest of the world.

Interactive Programming

Many programming languages offer interactive environments, that allow you write your code in little fast paced experiments. Iterative working to the max! The most basic form of this is the Read Evaluate Print Loop (REPL), which is a staple of languages like Python, Julia, R and F#. In the greater .NET ecosystem (which is pretty C# heavy) interactive programming hasn't been a thing, really. With the advent of .NET Interactive this has begun to change. Jupyter Notebooks - interactive, web based, coding environments, that allow to mix prose, source code and formatted outputs - have been the defacto standard for communicating experiments within the Data Science and Machine Learning community for a while now but mostly for scripted languages and not really outside of the aforementioned niches.

With its latest push to make .NET a target for Machine Learning projects, Microsoft has shown great commitment to make all common .NET languages (Powershell, F# and C#) work well in Jupyter Notebooks. It even went a step beyond and started building great tooling for VSCode, that makes it possible to run and edit .NET interactive notebooks directly in the editor. Their latest blog post - as of writing this - shows how to get started with .NET interactive in VSCode Insiders. I highly encourage you to try it out! While you're at it you can also check out the nteract desktop application which was one of the first apps I'm aware of, that allowed people to have a more integrated development experience while working with interactive notebooks.

All the sources I mention in this blog post can be found in this repo in case you might want to experiment with the code yourself.

A short disclaimer: please be aware, that everything connected to .NET Interactive is still pretty bleeding edge and therefore quite unstable. Nevertheless, right now is a good point in time to start using it cautiously and to provide feedback to the maintainers (or even fix some things yourself). If you find something in this post, that doesn't work for you anymore because of a change don't hesitate to reach out. I'll do my best to update it as soon as possible.

Default Formatting

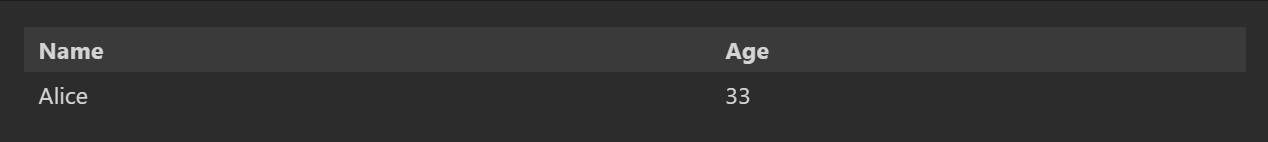

So when you write code, what do you usually do? I would guess that you write some functions, apply them to some values and get something back from those expressions. At least that's how it works for me. For a F# developer the things you get back are usually records, discriminated unions or Plain Old CLR Objects (POCOs). Because these types are so commonly used, .NET Interactive includes some sensible default formatting strategies. Let's look at a simple record:

type Person =

{ Name: string

Age: int }

let alice = { Name = "Alice"

Age = 33 }

alice

If a value is returned without being bound to a name (or without being ignored) .NET Interactive will display it. We could also use the display function to get to the same output.

This tabular view makes complete sense for records. It puts all the member names in the header and displays the values as a row. Even if you're not used to look at tabular data the whole day it is still understandable. So what about nested records? In the F# world we are pretty fond of composing more complicated data structures out of small and simple records. How would .NET Interactive handle the following?

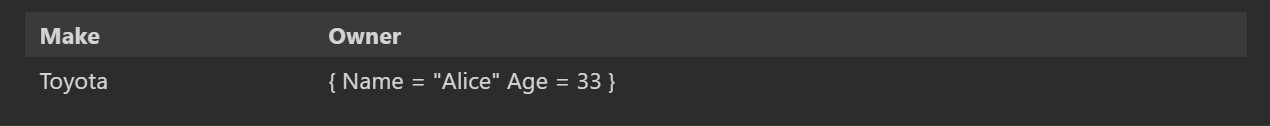

type Car =

{ Make: string

Owner: Person }

let alicesCar = { Make = "Toyota"; Owner = alice }

alicesCar

Nice! Displaying nested tables would be odd, so .NET Interactive was so kind to display the nested record similar to how we constructed it in code. So what about POCOs? In F# it sometimes makes sense to define a plain old class or struct. How does .NET Interactive handle those kind of objects?

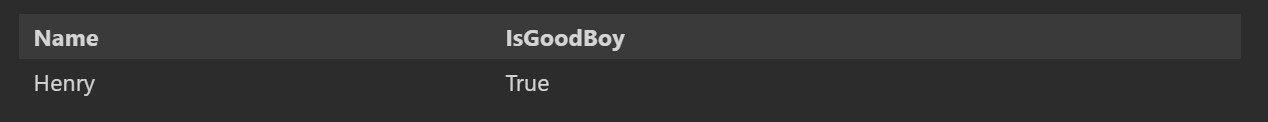

type Dog(name: string, isGoodBoy: bool) =

member _.Name = name

member _.IsGoodBoy = isGoodBoy

let henry = Dog("Henry", true)

henry

This looks like the output for the record above, doesn't it? Well it does because it uses the same formatter. Records are just POCOs with a bit of compiler magic sprinkled on top. As we'll see with the next example of a nested POCO this extra compiler magic pays of in interactive programming environments (besides being great in general, of course).

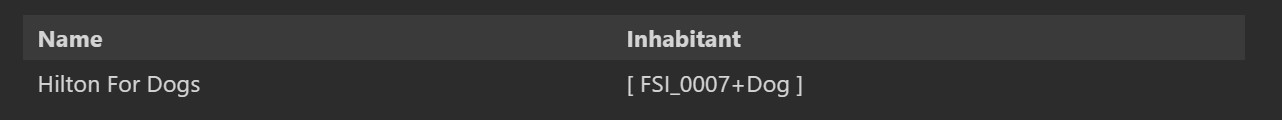

type DogHotel(name: string, inhabitants: Dog list) =

member _.Name = name

member _.Inhabitant = inhabitants

let hiltonForDogs = DogHotel("Hilton For Dogs", [ henry ])

hiltonForDogs

That doesn't look as nice, does it? Well it looks like this because .NET Interactive doesn't try to be extremely smart about displaying objects. It just goes through the top level properties, displays them in the table and basically calls ToString on the values in the row. This works well for F# records - because of the compiler magic - but not for POCOs. Let's look at Discriminated Unions next.

type Fruit =

| Orange

| Banana

| Apple

Apple

For simple case identifiers without any data .NET Interactive just displays the identifier name. In this case we will read Apple. How would that differ for more complicated union types?

type GiftBasket =

| EmptyBasket

| FruitBasket of Fruits: Fruit list

| SpoiledFruitBasket of Fruit list

let aNiceGiftBasket = FruitBasket [ Orange; Orange; Banana; Banana; Banana; Apple ]

let aNotVeryNiceGiftBasket = SpoiledFruitBasket [ Orange; Orange; Banana; Banana; Banana; Apple ]

display aNiceGiftBasket

display aNotVeryNiceGiftBasket

display [ aNiceGiftBasket; aNotVeryNiceGiftBasket ]

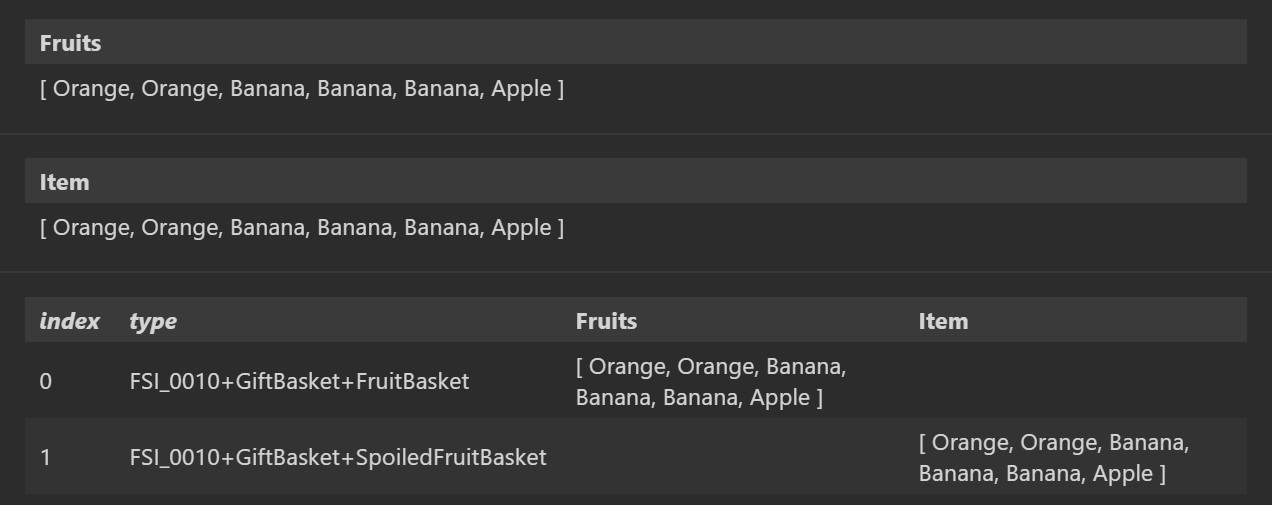

There's a bit to unpack here. The first line displays the data of the nice gift basket which is a FruitBasket. We get the descriptive Fruits table header because that's the name we gave to the field. For the SpoiledFruitBasket we did not specify this field name, so we'll get the standard Item label. It seems a bit odd to me, that we don't get to see which case identifier we're currently looking at. It gets even more odd when we see that the standard formatter displays the case identifier types correctly for lists. I'm not entirely sure why that's the case but I'll use my confusion about this odd choice to show how to register custom formatters.

Simple Plain Text Formatter

For me it should be super obvious whether I'm looking at FruitBasket or a SpoiledFruitBasket. So - only for this very special Discriminated Union - I'm going to register a formatter, that displays its standard F# string representation. .NET Interactive automatically loads all the libraries you need to extend it and exposes them globally for you. Let's take a look.

module GiftBasketFormatter =

Formatter.SetPreferredMimeTypeFor(typeof<GiftBasket> ,"text/plain")

Formatter.Register<GiftBasket>((fun basket writer ->

let formatted = sprintf "%A" basket

writer.Write(formatted)), "text/plain")

We don't really need to create a module here but it makes sense to use one if you open up more namespaces and don't want to pollute your notebook scope with the extra open statements. We can access the Formatter class because .NET interactive loads a couple of assemblies in the background (as I mentioned before). We can use it to set the preferred MIME type for the type we wish to format. I think about it like I would about content type negotiation in a web context: .NET interactive gets the request to display a value, looks at its type, checks its default MIME type and selects the fitting formatter for the MIME type. You have to force its hand sometimes when a preexisting formatter would have the greater precedence, that's why I explicitly set the preferred MIME type.

Now that we specified, that GiftBasket values should be formatted as plaintext we can register a formatter. The Register method offers a bunch of different overloads. Currently - as of writing this - they aren't really documented so I basically roll with the ones, that work for my use cases and are convenient to use. The easiest version I've found so far is the one which takes an Action<'T, TextWriter> delegate where 'T would be the type you want to format. In most cases we are totally fine by not explicitly creating the action delegate and defaulting to the much nicer F# lambda expression. I had problems with type inferences in some edge cases, though, so your mileage may vary 🤷♂️ Just remember, that you can always be more implicit in F# if you really need to and you'll be fine 👍

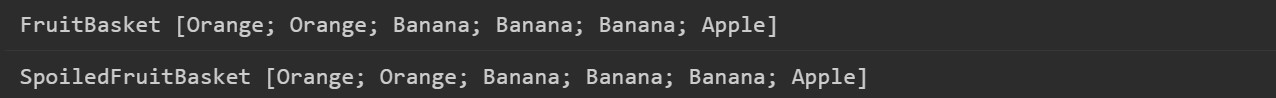

With the new formatter in place we can try out to display the different GiftBasket values again.

display aNiceGiftBasket

display aNotVeryNiceGiftBasket

Much better now! This example was - to be totally honest - not very useful, though. With the basics out of the way we can look at a more useful example.

Charting with Plotly.NET

On my search for a plotting library, that actually allows subplots (which XPlot.Plotly doesn't) I stumbled upon Plotly.NET. It started out (as many great science-y F# libraries) at the institute for Computational Systems Biology - CSB Kaiserslautern but was moved to the official Plotly organization some time ago. The current "approved" version is still in alpha but in general it feels much more mature than that.

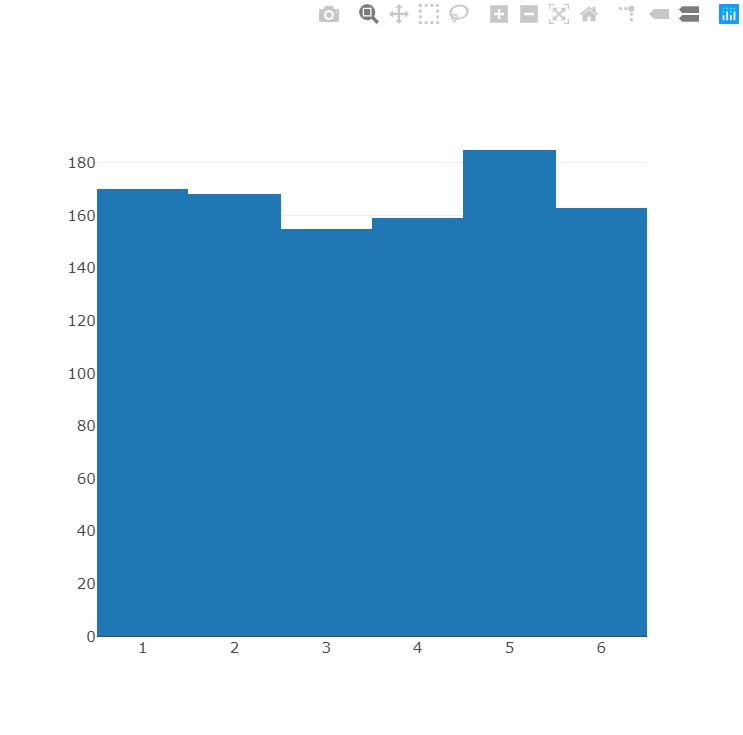

I often use plots for looking at how the values within a dataset are distributed. Just to get a general feel, you know? Let's say we roll a "random" die in .NET and want to see how many ones and twos and threes and fours and sixes we have rolled. I'd usually go and look at a histogram for that. In Plotly.NET, that's pretty easy to do.

open System

open Plotly.NET

let rollUniformDice (rnd: Random) =

rnd.Next(1, 7)

|> int

let rnd = Random(Seed = 1)

let diceRolls = List.init 1000 (fun _ -> rollUniformDice rnd)

diceRolls

|> Chart.Histogram

If we would be using XPlot.Plotly we'd be looking at a nice histogram by now. That's the case because the .NET Interactive developers wrote a formatter for us. They obviously didn't do so for Plotly.NET and so we only get to see some object properties and nothing else. What a shame! Good, that we learned how to write a custom formatter. Of course, writing the HTML and JavaScript interpretation of a chart would be everything but trivial. We can thank the library authors, that they've already done this for us. To get the whole thing working I basically had to call a single method - that's it. At least it would be if there weren't a bug, that - as of writing this - breaks a piece of JavaScript in VSCode. It could be patched on the fly, though. Lucky us 🍀

module PlotlyFormatter =

open System.Text

open GenericChart

Formatter.Register<GenericChart>((fun chart writer ->

let html = toChartHTML chart

let hackedHtml =

html.Replace(

"""var fsharpPlotlyRequire = requirejs.config({context:'fsharp-plotly',paths:{plotly:'https://cdn.plot.ly/plotly-latest.min'}})""",

"""var fsharpPlotlyRequire = requirejs.config({context:'fsharp-plotly',paths:{plotly:'https://cdn.plot.ly/plotly-latest.min'}}) || require;"""

)

writer.Write(hackedHtml)), HtmlFormatter.MimeType)

When we try to display the same plotly chart from before we'll see a nice interactive histogram. Neat!

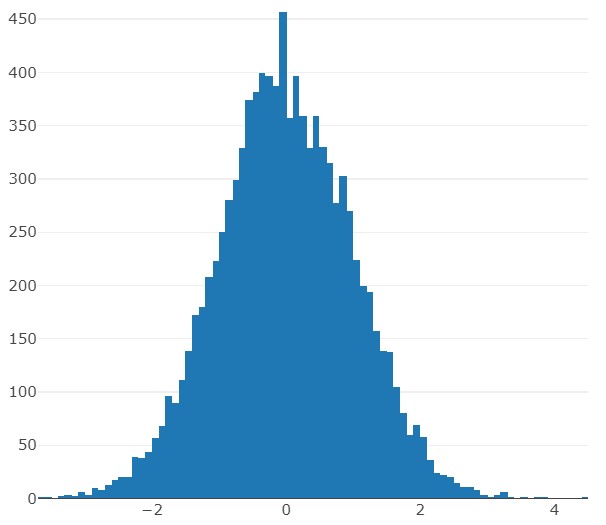

Looking at such a histogram, it doesn't take me too long to recognize, that our "dice rolls" are uniformly distributed. This makes sense because the .NET standard random generator is - in fact - a generator for uniformly distributed numbers. With this knowledge (and a bit of internet research) we can even build our own normally distributed random generator. Validating if it works would take some math I don't really know too much about, so I'd just take the more intuitive route and look at the distribution in a histogram. If it looks like a bell-curve it's good enough for me.

let normalRandom (rnd: Random) =

// mean of standardized normal distribution

let mu = 0.

// standard deviation of normalized standard distribution

let sigma = 1.

let u1 = 1. - rnd.NextDouble()

let u2 = 1. - rnd.NextDouble()

let rndStdNormal =

Math.Sqrt(-2. * Math.Log(u1)) * Math.Sin(2. * Math.PI * u2)

mu + sigma * rndStdNormal

let rnd = Random(Seed = 1)

List.init 10000 (fun _ -> normalRandom rnd)

|> Chart.Histogram

Looks good to me! Of course it is only an approximation because the used Box-Muller Transform isn't 100% exact but with large enough samples we can get really close to the ideal. The neat thing about interactive programming is, that we can just try to tweak the parameters, look at the resulting plots and iterate pretty quickly until we either try something completely different or are content with what we have.

So now, that we have a Plotly.NET, that works for us, how are we going to reuse it? We can just copy it from notebook to notebook (and I have done this a lot for this and other formatters) but that doesn't really scale, does it? The .NET Interactive team anticipated that and implemented an extension mechanism. Let's take a look at that next!

Writing an Extension Package

Writing a kernel extension for .NET Interactive is pretty straight forward, it has a couple of catches, though. Especially now while the project is still on the bleeding edge of development. I've built one or two extensions in the last couple of weeks, so I can at least share what I've found out so far. In its core every kernel extension is just a plain old .NET library you can load as a NuGet package. Go and take a look at the F# project I created for the Plotly.NET extension. Tiny, isn't it? Just one source code file and a project file. If you take a look at the source code you'll basically see what we've already seen in the code cell - with one important addition.

namespace Dotnet.Interactive.Extension.Plotly.Net

open System.Threading.Tasks

open Microsoft.DotNet.Interactive

open Microsoft.DotNet.Interactive.Formatting

open Plotly.NET.GenericChart

type PlotlyNetFormatterKernelExtension() =

let registerFormatter () =

// exactly the same Formatter.Register call we had before

interface IKernelExtension with

member _.OnLoadAsync _ =

registerFormatter ()

if isNull KernelInvocationContext.Current |> not then

let message =

(nameof PlotlyNetFormatterKernelExtension, nameof GenericChart)

||> sprintf "Added %s including formatters for %s"

KernelInvocationContext.Current.Display(message, "text/markdown")

|> ignore

Task.CompletedTask

Instead of a raw Formatter.Register call we define a type and implement the IKernelExtension interface which has one method OnLoadAsync. This method would take a Kernel object and return a Task. In my implementation I don't need the Kernel, so I discard it. Also, I don't have async operations in my code which allows me to just return a completed Task. Other than that I just check if I have a KernelInvocationContext - I don't know exactly when I wouldn't but I'm pretty sure, that if this can be null there are cases where it will be - register the formatter and print a message for the consumers of this extension, telling them what it does. That's it. No more work to do for us in this part of the project. As you might imagine, this wouldn't actually work without a little extra in the project file. Let's see.

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<!-- standard packable F# library props excluded for brevity -->

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Remove="bin\**" />

<EmbeddedResource Remove="bin\**" />

<None Remove="bin\**" />

</ItemGroup>

<!-- dependencies excluded for brevity-->

<ItemGroup>

<None Include="$(OutputPath)/Dotnet.Interactive.Extension.Plotly.Net.dll" Pack="true" PackagePath="interactive-extensions/dotnet" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

The official docs on writing extensions have some pointers on how to get started. They don't really talk about the extra bits you need in your project file so I thought we should take the time and do it here. I'm still unsure about the ItemGroup, that excludes items from the bin directory. I assume, that this is mainly meant for generated assets that could get referenced in the package but as they are very consistent with this even in extension packages, that don't have any generated content I'd just play it save and leave it as is. It didn't make any difference in my tests, though, so there should be no harm in omitting this.

The second addition is far more important. Kernel extensions are only picked up by .NET Interactive if they are contained within the interactive/extensions/dotnet folder of your NuGet package. You really have to specify this exactly this way or it won't work - no way around that. That's it. That's all the things you need to make your .NET Interactive extension sharable. I personally think, that this is super awesome. I've already seen people using Fable to embed React apps into interactive notebooks. With the power to transform any datatype into some web-digestible format the opportunities are virtually limitless.

Be aware, that as of now not all packages you'd need to build an extension are in the public NuGet.org repositories. They aren't private, though, so you can always try out the experimental bits produced by Microsoft. I took the NuGet.config file the .NET Interactive team is using internally and put it in the root of the solutions where I develop my kernel extensions which resolves all sorts of dependency issues. I'm pretty sure, that when the times come to officially release .NET interactive this step will become unnecessary.

A Shameless Plug for Deedle

Deedle is the most mature data frame implementation .NET currently has. Sure, there are others like Microsoft's own data frame or SciSharp's Pandas.NET but neither of them are currently out of their respective alpha stages. Deedle might have quite the learning curve but with a bit of training (and maybe a couple of example notebooks - just putting it out there) one can get really productive with it. I've been using it for a while now in .NET Interactive for some experiments and I've been pretty happy with it. Of course I had to write a formatter for it, which you can find here. It is still pretty rough and before I can even think about getting it into the official Deedle repository I need your feedback. So if you are as enthusiastic about the future of interactive programming in .NET, do me a solid and take some time to play with it. I'd be really happy about some feedback, that could help me to make this formatter as good as it can be for Deedle users. Thanks in advance!